Meeting Sally Mann: Art Work On The Creative Life

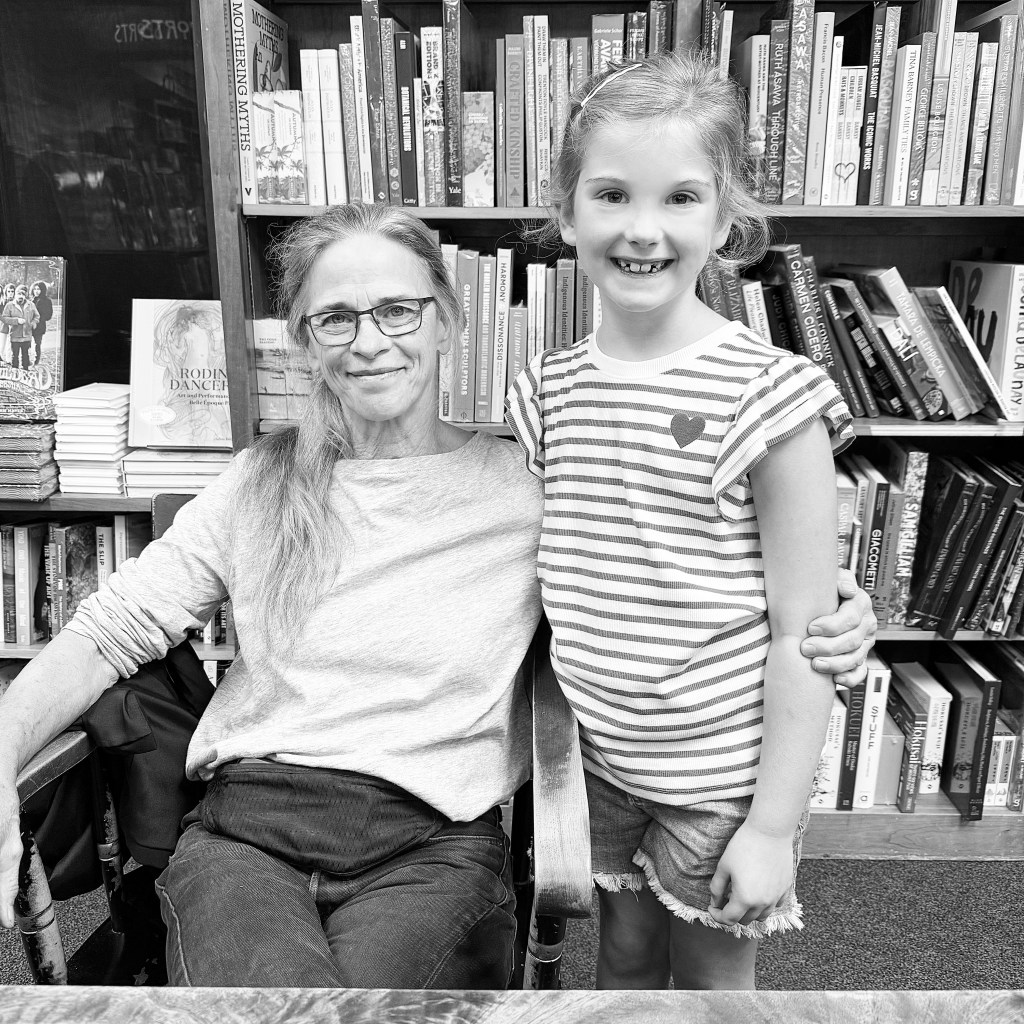

This fall, we all had the opportunity to meet Sally Mann on her book tour for her new book: Art Work: On The Creative Life. Sally kindly wrote a blurb for my book, and we began corresponding with each other, which is a dream, as she is one of my photography heroes. At the book event, Alex was even brave enough to ask Sally a question during the Q and A, and Victory came, too. Alex is a very creative being, and it has been so much fun to have her meet well-known artists who have made and and live a creative life—knowing it is possible. A few photos are shown below, along with some of my favorite quotes from this book, which offers a mix of illuminating stories, practical advice, and life lessons on being an artist, including insights about the hazards of early promise; the unpredictable role of luck; the value of work, work, work, and more hard work; the challenges of rejection and distraction; the importance of risk-taking; and the rewards of knowing why and when you say yes. I highly recommend this book for all creatives!

Below are some of my favorite quotes from Art Work. Perhaps they will inspire you, as Sally’s words have inspired me.

“So many of our fellow humans, unbeknownst to us, are quietly bearing a load of pain that would make Atlas groan with the weight of it. Despite outward appearances, most of us have an interior edifice of complex emotions, whose dimensions are unexposed, unexpected, and profound. And some of us are lucky enough to have ways to express that dark geometry, to tell our own unique stories.”

“Freedom is the scariest thing of all—when I encounter a blank calendar page, I will needlessly transplant the philodendron to avoid picking up the camera and making new work. But the discomfort of not making work eventually becomes so great that making pictures is less painful than not making them, even considering the looming uncertainty each time I pick up the camera. That looming—and, I believe, essential—uncertainty is the unshakeable companion for all of us who want to make art. Great art.“

“You say Yes even when you know, to your very bones, that you can’t do what is expected of you and that you are in way over your head. You say Yes because you will grow in ways you could never expect. And you might just luck out and get a photograph despite everything.”

“All I had to do was put my head under the dark cloth and my face to ground glass. That is all any of us ever have to do; pick up the paintbrush, the welding torch, the ball of moist clay, fire up the computer and start pecking. To defeat fear, I occasionally just set up the camera wherever I am, pull the dark cloth over my head, and look. Sometimes, by excluding outside distractions and creating aesthetic limitation, even artificial ones, I ease my fears that I will fail, perhaps in the same way Temple Grandin found relief from her anxiety by being pressed between two mattresses.”

“You take that first picture exactly as a writer bangs out that first line. Hemingway wrote early in A Movable Feast about gazing out over the roofs of Paris and exhorting himself to write. Basically, it’s simple: You have always written, you will write again, just write the one true sentence you know. Once you write that simple, declarative sentence, and ruthlessly cut out anything resembling what he called ‘that scroll-work’—in his case, a word processing more than two syllables—you go on from there. . . . Pick up your pencil, your camera, your paintbrush; find your story, keep it simple. Or let it find you, but keep going.”

“But I kept taking pictures. Perhaps the most important concept in that journal account of the trip south (and even in the 1978 letter) is that even though they were dumb pictures—and I knew they were—I kept taking them. Monkey at a typewriter. Sooner or later, there was going to be a good one, the monkey was going to get lucky, even if it was by accident.”

“But, in my case, despite being an unregenerate rebel most of my young life, I began to feel what Wordsworth called the ‘weight of liberty.’ Without quite realizing it, I began to give myself assignments; parameters within which to work. Like using just one shutter speed or one lens, or only taking pictures that had chiffon in them, or limiting my subjects to the age of twelve, or, most memorably, insisting on hand-holding my large-format view camera, making me the butt of jokes for years.”

“I am far from spiritual, but I have experienced, convincingly, the ineffable magic by which obsession, frustration, repetition, and serendipity miraculously transfigure that thin, Nabokovian slice of time, that tenth of a second, into something eternal.”

“What I see is: taking down the show and carrying it home and putting it back in its dear little box and, well, now what? What are we doing this for? Do you ever ask yourself that question? What do we really want? what is the thing that gives pleasure? What is the goal, after all? Where are the rewards when it’s all said and done, wouldn’t we rather be sitting out on the deck with a fresh gin and tonic in our hands surveying the kids gambolling in the sunset and patting the dog? I mean it? Do I care about New York? Shit, no. Do I care about and what gives me the most pleasure is that instant, when you turn on the lights and lift the film out of the fixer and turn the music up real loud and do a little crab step across the darkroom floor. I would just die for that feeling, that is it, for me, that is what matters and in the end, all work becomes ‘old work’ from that moment on.”

“For me, staying home and enjoying the simple life of a nineteenth-century Flaubertian recluse, which is what I do 99 percent of the time, helps with this approach, and perhaps something like it could work for you. Nevertheless, even today I find that I need to employ that still-serviceable protective covering, spun from the mendacious pluck, false confidence, and timeworn lies I wanted to believe, especially when I suffer rejections that sting. (Yes, I do, and yes, they still do.) All the while we keep working, making our art, whatever it is. It’s our job, just like any other job, only with longer hours.”

“So double bold that mythically bulging door, send away all the art-world impresarios and agents, do not succumb to jealousy or study the auction results, go back into your studio, sit at your desk, make your work, and ruthlessly toss out whatever isn’t good enough, for whatever reason. Do that for the next twenty-five years.”

“I try to figure out what I want next out of life and I just want more good work. I just want diversity and quality, that’s all. And the longer I work and the longer I push the limits of what I think I am capable or doing, the better I feel about being able to achieve that. Each time I sort of arbitrarily wrap up a project and begin to flounder about, wondering what on earth I’ll follow it with and will I ever do work that is as good, it always comes. Maybe not right away and maybe not without a few false starts and enormous doubt but it’s there and eventually I begin to hit my stride again and that feeling of elation and power and confidence takes over and the good flows. It’s true that some years’ work is better with a little embarrassment or chagrin but in the main, I think that the stuff is strong and it just keeps getting better. (You can tell where I am right now in the cycle—on a real roll . . .let’s talk about it again in about a year when I’m lost again. . .) In any case I wonder from time to time …”

“There are many ways to screw up; big ways, little ways, keep-you-awake-at-night ways. You will have your ways too, but mistakes are not all bad; if you haven’t made any lately, go out and make one. It will move you forward. Dog, Umbrella stand. Seven strides. Down the drive. And through it all, you will keep making your art, perhaps almost unconsciously, as if sleepwalking, because art is what you do.”

“It happens when I work, when I am taking pictures and my vision, even my hand, seems guided by, well, let’s say a MUSE. There is, at that time an almost mystical rightness about the image: about the way the light is enfolding it, the way the eyes have taken on an almost frightening intensity, the way there is a sudden, almost space-like, quiet, as if suddenly there was a weightlessness and an absolute vacuum. These moments nurture me through the reemergence into the quotedian . . . through the bill paying and the laundry and the shopping for soccer shoes . . . Although I am finding that I am becoming increasingly distant, like I am somehow living full time in those moments. I find my children’s faces turned inquisitively up to mine, floating almost like underwater plants distant and unrecognizable, the spoken question unheard, the answer impossible.”

“Not to come over all woo-woo, but maybe we artists are merely a convenient vehicle for our work to express what it needs to say. We carry it like a self-replicating virus, or like that species of Hymenoptera, the burrowing wasp described by Proust, which guarantees the survival of tis offspring by providing them with their paralyzed host’s living flesh upon hatching.

“Another way to think about it is to situate creativity within the Platonic doctrine of recollection, which asserts that we do not “create” so much as provide the vehicle for the release of knowledge that came bundled with us at birth. In this scenario, the work exists within a universal reserve of latency, of inchoate and unformed possibility that awaits the artist’s hand to be physically realized. We can only hope that what our work wants to say is worth many sacrifices we make for it to do so.”

“Despite being a person who generally likes to be in control of both my body and my mind, I relax that control where art-making is concerned. Trancelike, I allow myself to be ensorcelled as surely as Odysseus by Calypso and welcome the diversion for as long as the enchantment will last. It’s possible this only works with art. In almost any other enterprise such a high level of uncertainty would be ruinous; you would never begin a statement in court without knowing how you were going to close, but when making art, a tolerance of uncertainty is almost essential.”

“Those qualities in your work that bother people most are often precisely the ones that should be cultivated, pushed so far out on the axis of vice that they come around to be virtuous.”

“Cynical sophisticates scoff at the belief that if you make your true work with the purest intentions, your sincerity scoff at the belief that if you make your true work with the purest intentions, your sincerity will be rewarded even by the jaded art world, but you know what? I kinda buy that. Do the work of your earnest heart, with all your body and soul, for as long as you breathe and with as much craft and creativity as you can wring from your every filament, and you will have made art. Your art.”

“From my first roll of film and 1969, and in my earliest poems, so maudlin they could have been optioned for a high school musical, I was drawn artistically to the things that felt emotionally significant. And in that process, I found that the past had unavoidably shoehorned its way into the inquiry and rendered my work occasionally mysterious, even to me. I feel as inextricably connected to the history undergirding my present as the old woman in a Chekhov short story who is caught nosily weeping over a biblical incident as if it had happened yesterday. Her younger observer, a theology student muses: ‘The past . . . is linked to the present by an unbroken chain of events all flowing from one to the other.’ When one end of that chain is disturbed, the other trembles, like a spider’s web at the distant, tentative touch of her prey.”

“And now we’re there, the place you knew we’d get to eventually. Why else would I have mentioned, right at the beginning, the word I said I was never going to say again in this book? Like Checkhov’s loaded gun, you knew it was going to go off, sooner or later, before the final curtain. But not before the strut fret of the main characters: luck, organization, technique, words (on actual paper), patience, tenacity, risk-taking, moral questioning, and finding your story–or letting it find you–plus, of course, character building suffering. But all those players have had their moment in the spotlight, and here we are.”

“When does will become passion? On page 61 in my Quotes list. . .is somewhat embittered, but germane, statement form the inventor of the Post-it note: ‘In 1931 I won a Carlton Society Award, which is like winning the Nobel Prize.’ The award reads: ‘Arthur Fry, for the novel and creative approaches to the development of products based on his repositionable adhesives and for his tenacious dedication and commitment to the program that resulted in Scotch brand Post-it Notes.’ Tenacious, huh? The difference between success and failure. I was stubborn until I became a success. Then I became tenacious.”

“It is unfortunately essential that those hours comprise difficult acts, of increasing miserableness, in order for any of us to improve. We’re back to suffering here: if it were easy, then everyone would be doing it.”

“The passion for making the work exactly right seemed existentially imperative to me, as I hope it does to you.”

“Leave your fearless trace, dove sta memoria, because beauty matters. As an artist, you are a sensitive filament pock up unique frequencies and making the work they evoke. And if you are lucky, when that work is released, it will find untingled nerve endings out in the world and lustily tingle them, manifesting indelible truths in which someone will one day find beauty. That is our job.”